Menu

- 10am - 4pm, Mon to Sat

- Adults: £8 Under 18s: £4

- Under 12s/members: FREE

- Pensioners/students £7

- Birchburn, Scotland

- 01445 731137

- JustGiving

H.M.S.TRINIDAD

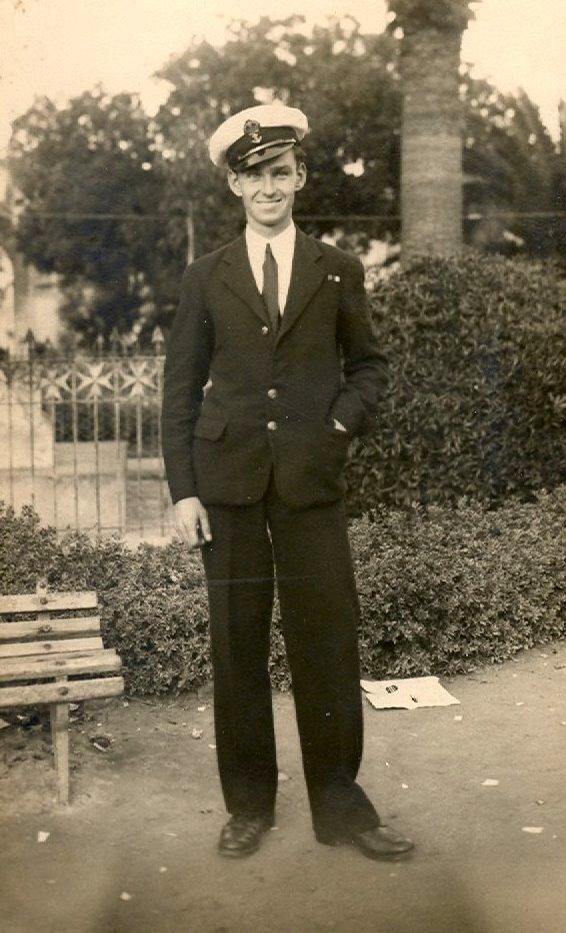

Herbert John St. George Soper

I first saw TRINIDAD when she was a collection of frames, girders and steel plates gradually taking the shape of a Colony Class Cruiser in no.3 building slip in Devonport Dockyard. I was Herbie Soper – 2nd year naval shipwright apprentice who, with some others of my entry, had been assigned to her to learn the rudiments of the trade. We were an unruly crowd and spent a lot of our time generally misbehaving when we could avoid the sharp eyes of the chargeman and inspector. Under the ship among the keel blocks we had what were known in the navy as ‘cabooses’. Here we would hide our girlie magazines and the stronger stuff that we didn’t want mother to see. We also boiled and fried shrimps which we caught off the slip jetty.

Meanwhile the serious work of building TRINIDAD went on. The ship grew, war was approaching and many men were sent to North Yard to attend to the more pressing problems of getting the ships to sea. I went with them for a time but returned later with my instructor, Charley Hosking, who was sent back to deal with the formidable task of lining in the propeller shafts, engine seats, shaft tubes and shaft brackets. It was then, as it is now, an intricate task…the centre of the shaft being represented by taut piano wire which is set at a rake measured in thousandths of an inch. Some time later when TRINIDAD was chasing three German destroyers while protecting PQ13 convoy she attained quite an astounding speed and I have since reflected that this was due in some part to the accuracy of Charley Hosking’s work. He was a slow ponderous craftsman with an agile brain who tolerated my peccadilloes with much patience. At this time TRINIDAD was camouflaged in a mosaic pattern of varied colours…far different from the seagoing grey and black stripe effects.

I was there with Charley swinging a maul to ‘set her up’ in the hours prior to launch. ‘Setting up’ consists of gangs of shipwrights driving large wedges called ‘slices’ under the bilge ways. This literally ‘sets’ or lifts the ship up off the keel blocks which are then removed as the weight of the ship is transferred to the bilge ways. Eventually she was launched and taken to North Yard to fit out. I left her and rejoined her some months later to learn riveting and caulking. My friends and I were together again and we learnt how to handle the large machines which were used to ‘knock back’ the large ¼ inch steel rivets in the armoured decks. We were as ill-behaved as ever and I had discovered a little known fact when I accidentally fell into no.7 dock while docking a destroyer. You are taken, dripping wet, to the Dockyard surgery. Your clothes are removed and you are examined by the doctor, given a brandy and sent home for the rest of the day in an ambulance.

The number of apprentices who fell into the water off the decks of TRINIDAD was ludicrous. The brandy and day off were tremendous attractions.

The war had now taken a serious turn and the Dockyard was being bombed. The ship was in the last stages of fitting out and I think I am correct in saying that she was hit by a small bomb on her quarter deck during that period. I do recall one sunny afternoon when Plymouth was attacked by a number of German bombers with fighter escort. Several bombs were dropped…most of which went into the River Tamar. They narrowly missed the large French submarine SURCOUF. Unfortunately some bombs fell on Goschen Street outside the Dockyard and I think some people were killed. There certainly was considerable damage to the houses in the street.

Eventually TRINIDAD was commissioned and went to sea in the autumn of 1941 at about the same time that I entered the Royal Navy properly after having served a shortened apprenticeship. I served a period of training and I didn’t see the ship again until I was drafted to her with a ‘pier head jump’ ie. drafted in the morning and on the train in the evening with bag and hammock. Shipwrights also had to carry large tool boxes full of tools. A number of us travelled from Plymouth to Thurso…embarked on the steamer across the Pentland Firth and were temporarily accommodated in a ship called DUNLUCE CASTLE. We were transferred to a ship call BLENHEIM which was on its way to Iceland.

I saw TRINIDAD again in Hvalfiord. She was anchored with a number of other ships and I took my place in the shipwrights staff as a replacement for a man who had been invalided out with tuberculosis. I was appointed to the artificers mess which was located on the forecastle deck next to the crew’s recreation space. There didn’t seem to be enough to eat and it was cold but I did my best to settle in. I went ashore to the Nissen hut canteen and drank some Canadian beer…Black Horse I believe it was called. Although I was a reasonable drinker I found it quite strong. There are very high and low extremes of tide in Iceland and it is a precarious business climbing down the ladder to the liberty boat, particularly after having had some Black Horse beer.

Eventually we went to sea and I experienced sea-sickness. Not the clear and complete sickness from which one recovers quickly but the interminable lethargic nausea which seems to have no end. As the youngest in the staff (I was 20 years old and 5th class ie. the equivalent of a leading seaman). I was given all the unpleasant tasks. I was ‘elected’ to the prize boat crew and also the cable party. I am a little vague about the early days aboard TRINIDAD. We took a convoy to Russia and lost the destroyer MATABELE and some other ships. The men who survived the sinking were frozen solid in the water within minutes. I remember ten day patrols during which we roamed the Arctic Ocean and where else I know not. I do remember the endless gales and crashing grey and green seas…the interminable cold, snow and ice and the endless lurching of the ship. When I was on duty in the damage control HQ in the marines mess deck I used to spend my time watching the roll indicator which generally had a steady swing of 20-25 degrees in northern latitudes.

The shipwrights’ shop was in the ‘waist’ of the ship and during the roughest weather we were forbidden to go on to the upper deck. Green seas pounded the structure all the time. She was a ‘wet’ ship. Later ships of the class had bulwarks fitted to protect the upper deck but TRINIDAD only had guard rails which were bent regularly. On one occasion when no-one was allowed on the upper deck I was edging my way aft to the shipwrights shop when a frightening wave came inboard, picked me up in it’s crest, subsided when the ship rolled to port and deposited me on top of the torpedo tubes, wet and shaken. I was more respectful in the future.

During one particular storm we had been hit heavily on the forecastle with a huge wave. We found later in harbour that the deck had been compressed with the result that the pillar supports in the capstan engine compartment were bent an inch or two out of line. This caused the capstan and cable holder bearings to run hot and the next occasion we left Hvalfiord the capstan engine broke down under the strain and we were forced to rig hand capstan. Rigging hand capstan consists of inserting wooden capstan bars into sockets in the middle line capstan and securing them together with a rope lashed around the ends. This lashing operation which is carried out in a particular fashion is called ‘passing the swifter’. It caused some consternation the first time that we did it because some of us were unsure of this old naval drill. Little did we know that we would have to do this on several occasions. The first time we made a gala occasion and the Royal Marine Band mustered on the forecastle while a watch of the hands trudged around the capstan in their task of raising the anchor. We were anchored with some US Navy ships at the time and it caused some amusement at the antics of the eccentric British. It caused greater amusement later on because all the wind instruments froze up one by one and we were left with a Royal Marine violinist standing on top of the capstan. Eventually his fingers were too cold to find the chords and the sole surviving member of the band as we completed the raising of the anchor was the drummer who had no problem in the rapidly falling temperature.

Because of the cold on these patrols I had taken to wearing a red goalkeeper’s jersey over my other clothes. In the silent hours I used to wear a pair of white plimsolls that had been issued when I was a naval shipwright apprentice. I was soon admonished by Harold Crocker the senior shipwright in the staff. He said to me “Where do you think you are? On your father’s yacht?”

We spent some time in Arctic waters and although I had a sheepskin coat and sealskin helmet, mittens and sea boots it was still a frigid task chipping off blocks of ice from the fittings on the forecastle when the sea permitted us to get that far. The ventilation system was fitted with steam heaters which increased the temperature inside the ship but unfortunately because of the difference outside also increased the condensation. In the forward mess decks the water sloshed around as the ship rolled. Because of the perpetual Arctic twilight the deadlights were always screwed down. This increased the foetid atmosphere and on parts of the inside of the hull there was a coating of mildew.

We went on a trip near Norway covering some minelayers. I can remember on one of the better days in the sunshine seeing a number of mines bouncing past the ship. They must have broken loose during the mining operation. Another operation involved going in with LONDON to contact and shadow TIRPITZ which was reported to be at sea. I remember the Captain’s voice over the loudspeaker system telling us what we were involved in…and the details of the operation gave us a feeling of apprehension.

Weeks followed weeks of frigid cold. I was still in the cable party having a grandstand view of entering and leaving harbour but having to suffer for the privilege. The incident of the Royal Marine Band playing in the first occasion of hand capstan had been a joke. Later occasions proved it to be not quite so funny. We were anchored in Seydisfiord in April 1942 preparing to leave as escort to convoy PQ13 bound for Russia. Darkness was upon us and the Aurora Borealis was hanging in the sky like psychedelic curtains above the dark sinister cliffs. We were anchored in very deep water and hopefully we switched on the electric capstan to weigh anchor. After a shackle of cable had been raised we had to resort again to hand capstan because of the excess strain on the bearings caused by the distorted deck. We had taken on fuel oil from a fleet tanker. As she was moving away she nudged us on the starboard side of the forecastle causing a small fracture. The wind was very strong and ice cold. All on the forecastle deck were dressed in the usual Arctic rig. We had an occasional cup of thick ships cocoa which helped to keep up our spirits in the face of what every man knew lay ahead. The sailors on the capstan bars trudged around slowly raising the anchor one link at a time like Nelson’s time. This, of course, took hours and the rest of us stamped around frozen…no joke this time. Eventually we moved out of the fiord into an ever increasing gale. When daylight came we formed up with the convoy and with our other escorts moved off hopefully. The seas rose and the rolling of the ship got worse. Our roll indicator in the damage control HQ registered bigger and bigger rolls as we moved north. We had a slightly depleted ship’s company because about sixty of the senior members of the ship’s company had been sent off on leave before we left. Our Chief Shipwright Nick Aherne was one of them and his place was taken by Harold Crocker the senior hand.

We had been having large seas over the forecastle for some time now and I had been sent forward to one of the boson’s stores in the forecastle to attempt to plug the leak in the deck which we had sustained in Seydisfiord. I doubt if there was a worse part of the ship to be in at this time with the bow rising and falling five or ten feet in a regular rhythm. I was a sad young shipwright working on this leak but Harold Crocker insisted that I carried out the job properly. I did my best with wood wedges, oakum and red lead. The storm increased as we approached Jan Mayen Island and it was every ship for herself. Some of the merchant ships were suffering worse than we were because of the large deck cargoes which some of them carried…tanks, planes and guns.

I remember one incident which demonstrated the power of the sea. Bill Strong and I were peeping out of the shipwrights shop and he said “Look at that!” A large object flew through the air in a wide arc into the sea like a jet propelled dustbin. We discovered that it was the large hawser reel which carried the ship’s towing wire…quite a formidable object to be wrenched clear of the deck by the sea. The storm continued unabated. Seas were mountainous, visibility was low and it was getting progressively colder.

The weather was our undoing. When it finally abated we discovered that the convoy was scattered over 180 miles and we started the dreary process of rounding up our ships, assisted by the destroyers. Finally we had them in some order again. One Saturday we were picked up by a shadowing German aircraft…a Blohm & Voss reconnaissance plane from Norway. This, we knew, foreshadowed an attack. During the afternoon we were attacked by Junkers 88 dive bombers and Dornier torpedo bombers (details scanty). TRINIDAD escaped except for a few bomb splinters in ‘A’ turret and in the vicinity from a near miss from a bomb. The attacks continued throughout the afternoon finally breaking off, to our relief.

We turned away from the convoy during the night in an easterly direction because we were expecting a surface attack and we were endeavouring to place ourselves between the potential attackers and the merchant ships. We carried very primitive radar…called RDF in those days. On the following day, around ‘tot time’, we were going through one of those snowstorms and the radar picked up some ‘blips’ which were deduced as being unfriendly ships. The guns were alerted. We had been at action stations for over 24 hours. Suddenly the snow cleared and we observed three enemy destroyers travelling parallel to us at 2000 yards range. All available guns opened up. Below decks, we in the damage control parties prepared our gear and lay on the deck as directed by the officer who gave a running commentary from the bridge over the loudspeaker. I was in the vicinity of ‘X’ barbette on the lower deck. Everyone was lying on the deck except one man…a leading stoker who was standing in the middle of the deck. He laughed at everyone lying there. We must have looked ridiculous.

Suddenly there was a terrific crash accompanied by a heat flash. Steel splinters sliced across the deck. The lights went out and the sea rushed in. As the ship heeled to port a fire main and a high pressure air main had burst…to add to the general noise and confusion. As the sea swirled in everyone thought that our time had come and rushed for the ladders. For a minute or two there was minor panic. A fire had started in the cabins and all was confused. The ship was moving at a terrific speed and the vibration was tremendous at the after end. In a few minutes we had reassured ourselves that we weren’t going to sink and returned to our stations. The minor fire which had started had been extinguished by the sea and the burst fire main. Emergency lights were soon rigged and we discovered ourselves ankle deep in water. We had been hit by a shell on the port side of the cabin flat. The shell must have burst on impact because there was a fair size hole in the ship’s side approximately 5 feet by 5 feet and a few inches above the waterline. The water had initially swirled in as the TRINIDAD heeled over in a sharp turn to port. Now that she had straightened up on more or less an even keel it didn’t appear to be as bad as originally thought. We had a casualty though. Lying on the deck was one man who was very badly wounded. It was the leading stoker who had been standing up. The lower part of his body was in a terrible state as if he had been attacked by someone with an axe. Blood was welling and spurting from his wounds and he was moaning in pain what appeared to be a woman’s name. We did what we could for him and sent for the first aid party but he died very quickly.

We had to do something about the damage. We repaired the fire main and the high pressure air line and then turned our attention to the hole. There was an acrid smell in the air primarily from the shell which had hit us but also from the smoke of our own guns which were firing continuously. As we contemplated, the hole blast dust into our faces as we plugged the hole with a patchwork of hammocks. We needed something substantial to brace them into position and I suggested to my mate, shipwright Waldron that we use the door of the captain’s cabin. It was of stout mahogany construction compared with the flimsy and jalousied doors of the ordinary cabins. I was to have to answer some awkward questions about that door later.

All the time a running commentary was being given. There was a shout “Look out below…torpedoes!” Once again we dived to the deck and covered our heads with our hands. There was a tremendous explosion and the ship jumped like a wounded animal. Once more panic. We rushed for the nearest hatch and scrambled up top. After a few minutes it became clear that the ship wasn’t going to sink immediately so we resumed the work of plugging the shell hole. Occasionally the water swirled in around our ankles and this made us move faster. Eventually we had a patch of sorts composed of hammocks with the captain’s cabin door shored against it. We hadn’t realised it at the time but we had been hit with two shells. However we moved forward to see if we could assist.

We had been hit on the port side by a torpedo which had ripped the 2 inch armour deck across and blew a hole out of the starboard side. The main explosion was in the Royal Marines mess deck and the compartments below. Of senior consequence was the damage to central headquarters which had been reduced to a shambles by the blast. The ship was on fire and we couldn’t get near the area of the explosion for some time. This hampered rescue operations. TRINIDAD slowed down and was obviously crippled. We were forced to rejoin the convoy and, in fact, be protected by the ships we had been charged to protect. There were men killed, wounded and trapped near the vicinity of the torpedo damage. Oil fuel tanks had burst and flooded many compartments. Several men were rescued with great difficulty from some of the lower compartments. Bert Tew, the shipwright officer, was responsible for getting some men out of the lower switchboard where oil fuel had poured from the vent trunks. We entered ‘A’ boiler room where there had been some damage from the torpedo explosion. Wood shores were used to advantage where possible but nothing could be done about the slab of ship’s side armour which had lodged itself in the boiler. The fire from the explosion was extinguished and some hours later there was an eerie silence down there broken only by the clang of a smashed trunk which swayed with the roll of the ship.

The situation aft where we had been hit by the two shells appeared to be under control. Services such as fire mains were again working. The large shell hole which had been plugged with hammocks had now frozen over making it more or less watertight. The other shell had hit in the medical store and appeared to have caused less damage. Apart from a few holes in the vicinity which we plugged up and caulked with oakum it had been contained inside the compartment which was watertight.

Some of us went on to the upper deck where the cooks were distributing currant bread. There seemed to be an enormous stock of it. The port torpedo tubes had disappeared mysteriously over the side as had some of our Carley rafts. We discovered later that in the hectic moments when we thought that we would sink the ship’s boatswain, Dickie Bunt, had instructed his ‘yeoman’, “Nutty” Newton, to cut some rafts adrift …just in case. As it transpired we didn’t need them and Nutty, who had been in a previous action in EXETER against the ADMIRAL GRAF SPEE, got frostbitten in the process. It was still bitterly cold and the sea, although not stormy, was rough enough.

The loss of the damage control HQ had been a setback and plans for the counterflooding to combat the list to port were a little makeshift. However the ship was set to within a few degrees of upright. Our counterflooding had the effect of making TRINIDAD a little unstable and we wallowed slightly in the swell.

Eventually we arrived at Kola Inlet and were greeted by the welcome sight of Russian tugs near the Russian naval base at Polyarny. We were slightly disconcerted by the Russian habit of weighting their heaving lines with 1 inch bolts instead of the more conventional ‘monkey’s fist’ favoured by British seamen. We anchored in the bay while arrangements were made to dock the ship in a newly constructed concrete dock which had been planned for merchant ships. There was some doubt whether a ship of TRINIDAD’s draught would clear the sill at the dock entrance but luckily we did it with inches to spare. We were accompanied into dock by large ice floes which hampered us slightly.

The Russians didn’t have square section timber to give us to provide shores for the ship’s docking but they did provide us with some long pine logs from which the branches had been lopped.

One of our problems in breast shoring the ship was that we didn’t have enough men who knew about the technique of docking a ship. This was normally performed by experienced dockyard men. However all the shipwright staff joined in. Small sledge hammers called mauls are normally used in the operation but we didn’t have more than two or three aboard the ship. The operation was under the control of Shipwright Officer Bert Tew and went off admirably considering it was accomplished with a few shipwrights, blacksmiths, plumbers, painters etc. moving from shore to shore using much smaller hammers to drive home the wedges which hold the shores firmly.

When the water was cleared from the dock we examined the torpedo damage. There was the familiar large jagged hole, dripping with oil fuel, exposing the torn, chaotic inside of the ship. The explosion had torn a large hole in the port side, slashed across the ship ripping the armoured deck across like cardboard and burst through the starboard hull. The blast had flashed upwards and the side of the hangar was damaged. Some of the ship’s side armour was hanging ragged and a large slab had torn its way into the forward boiler room to put it out of action and reduce our speed. The irony of this was that we discovered later that this was one of our own torpedoes. Certainly a tribute to the effectiveness of the explosive.

An urgent signal was sent to the UK for some steel plate to repair the damage.

Meanwhile the grisly job of clearing the bodies progressed. The shipwright staff had the job of making the coffins. We made them of plywood with one-inch holes in one end. Each body was contained in a canvas sack as were the pieces of bodies. Finally the coffins were weighted with shells before being screwed down. We lost thirty two men that Sunday but we didn’t have to make that number of coffins. In the weeks which followed we were to find further human remains. Arrangements were for burial at sea. The coffins were taken out by the destroyer ECLIPSE to the mouth of Kola Inlet.

The cruiser LIVERPOOL (or SHEFFIELD) arrived from the UK with some heavy steel plates. We were joined by Constructor Commander H. Skinner and a constructor lieutenant who were on the fleet staff. They had been sent up to organize temporary repairs which were to be carried out by the Russians with ship’s staff assistance. Soon after he arrived Commander Skinner asked me if I had been a naval shipwright apprentice. I replied that I had. “You can weld and burn then?” “Yes sir”. “Contact the Russian interpreter Zhandikov and he will arrange for you to join the Russian repair workers”. After some days I found Zhandikov in the wardroom drinking gin. He appeared to be quite impressed with our capitalist hospitality because every time I went to consult him he was annoyed at being disturbed. He directed me to work with a group of workers which consisted of some fairly old men, girls and very young boys who were mainly employed on welding and burning. I had to familiarize myself with unfamiliar equipment and strange people. I got on well with the girls and the youngsters in spite of the language difficulties, but the men were extremely difficult. They were morose and ill-tempered generally. We got down to the business of sorting out the wreckage. The explosion in the fore end had severely damaged the cold rooms and the meat that we had in storage was severely impregnated with oil fuel. It was of no use to us but the Russians carried it away. We found out after a while that their need was greater than ours. After a time they supplied us with some reindeer meat. This is not exactly venison…rather like inferior beef. The Russians were having a tough time. The German lines were only twenty odd miles away and occasionally we could see the flash of guns over the pine forests in the distance. We had many air raids and it was decided to make the ship as inconspicuous as possible. We painted the decks white and spread nets over the guns and directors to disguise ourselves. The white decks blended in with the thick snow and ice with which we were surrounded. I remembered TRINIDAD’s earlier disguise before she was launched when she wore a costume of many colours to fool the enemy.

At the head of the dock the Russians had an anti-aircraft gun dug into the thick snow. It was surrounded by a barricade of sandbags and had an armed sentry on the perimeter to compel the British to keep their distance. They shouldn’t have bothered. It was a British 3.7 anti-aircraft gun similar to the hundreds which merchant ships and their escorts had struggled to bring to them together with the Hurricanes and British and American tanks, all of which were rushed to the front for use. We often saw these planes flying over emblazoned with the Red Star insignia. One day a Royal Marine wandered too close to the gun enclosure and was shot at. I suppose one could say that they just didn’t understand but we found in Polyarny, Rosta and Murmansk that their often open hostility and ingratitude was difficult to bear with equanimity. Hundreds of men had lost their lives and would lose their lives in the future to help them. We knew about it but they appeared abysmally ignorant. We learnt a few words of the language “Da” (Yes), “Niet” (No), “Dobray” (Good), “Nien Dobray” (No good)…a very common phrase. One day a young man asked me for cigarettes. I indicated almost apologetically that I didn’t have any on me. Politeness was wasted on him. He spat at me and said “Nien Dobray Gospodin” (“No good comrade”) (The Russian words for good/no good/comrade are not exactly as stated so these Russian words may be Russian vernacular). The girls were more amenable. They wore ugly felt boots…as did everyone except the officials who had patent leather ‘galoshkas’. They also wore padded quilted coats. Charming as they were they smelt terrible. Several of them sported gold teeth. The young boys who were doing mens’ work appeared to be very bright and intelligent. Inflation was fantastic. We were allowed to change some of our money into roubles at the rate of one rouble for 10½d. A man gave me twenty roubles one day for a box of matches. A bottle of vodka was the British equivalent of £15. The snag about roubles was that we weren’t allowed to change them back into British money so this very effectively curbed any budding black market in commodities.

Without any doubt they were different people from us. One day we went ashore in Murmansk. There was a short and nasty air raid. In one of the streets a few people were killed. After the raid the bodies were rather unceremoniously pushed into the gutter to allow horse drawn sleds to pass. Every time we were raided by bombers the Russian dockyard stopped work…not necessarily because of the danger or to enable men to go to the shelter. Work stopped simply because some invisible hand pulled the switch controlling the power. Our staff worked closely with a machine shop in the dockyard preparing steel plates. When work stopped we would sit down and converse in sign language with some of the less hostile workers. They were very sombre. Looking at it in retrospect I suppose they didn’t have much to be happy about. I never heard a Russian sing or whistle as we did. There were no seagulls close to shore. We were told that they shot them for food. The birds learnt the hard way and kept their distance.

I was still having difficulty with Zhandikov. He couldn’t understand why I couldn’t leave him alone to his socializing. There were some difficult problems of communication. Eventually the damage was partly cut away and a large patch was welded over the hole caused by the torpedo. We were to discover later that the patch wasn’t watertight and we left a trail of oil fuel…a certain guide for the enemy U-boats and planes if, indeed, they needed one. The key ratings had returned from leave. Chief Shipwright Dick Aherne was one of them and he was saddened by the news that his stand-in, Harold Crocker, had been killed at his action stations in the damage control headquarters. It might have been him. The shell damage was patched by myself and shipwright Alfie Brenton and eventually we undocked ready for sea. We embarked some survivors from EDINBURGH and several merchant navy survivors of various nationalities who had been in ships sunk in various convoys coming to Russia and had been housed in the rather grim Polyarny naval camp. We were also to take some Russian naval staff as far as Iceland en route for London. It was our intention to go to the United States for refit.

We anchored in Kola Inlet still a bit doubtful about our prospects because one boiler room was virtually out of action. We were bombed on Sunday afternoon at tea time and the ship rocked with a near miss. The enemy was certainly aware of us. A few days later TRINIDAD prepared to leave Kola Inlet with four destroyers in company. It was May 1942 and the time of ‘midnight sun’ had arrived. Whereas back in December we had had a very short day, now we were approaching the very short night. The sun, when we saw it, appeared to sink to the horizon and ‘bounce’ up again giving us almost perpetual daylight. Kola Inlet was very deep. Once again we rigged hand capstan and it took some hours to raise the anchor. We left at about midnight and steamed out of the inlet as fast as we could with one escort. We reached the open sea and headed north. The weather was clear at first with a few clouds. We had intermittent light snow storms blowing down from the Arctic. There wasn’t a lot of room for our passengers some of whom favoured the galley flat for obvious reasons. Apart from the sixty men from EDINBURGH we had several negroes and lascars, many of them with fingers and toes missing due to frostbite. Admiral Bonham-Carter hoisted his flag in TRINIDAD.

We hadn’t been at sea for more than a few hours when we were picked up by a shadowing enemy plane. She lurked in and out of the clouds which were dotted around the blue sky. Sometimes to get out of anti-aircraft range she flew low on the horizon around and around in a continuous large circle…watching. We didn’t have long to wait before the Junkers 88s arrived closely followed by the Dornier torpedo bombers. A series of attacks started which were to last all day until midnight. Down below we had been at action stations since we had put to sea and we had nothing to do but wait…lying on the deck in our duffels and sheepskin coats, playing cards and reading, trying to avoid the crash of the bombs and the frantic turning and twisting of the ship. We knew that we were in a perilous situation and tension was barely concealed. One of the unpleasant things about being in a damage control/ fire party below decks is that you have to wait for damage. Your part in the proceedings starts when the ship is hit and we all know the chaos that that brings.

Occasionally the attacks broke off and we were able to relax and eat some corned beef sandwiches and drink ships cocoa.

I remember being a quarter of the way through a large mug of cocoa coloured dishwater before I realised my mistake. The bombing resumed and continued through the day while we hoped for the occasional snow showers to hide us. In the evening we reached the edge of large fields of pack ice and the attacks intensified. We were almost getting used to the bombing when there was a terrific explosion forward. The ship shuddered and lurched and some of the lights went out. She immediately started to take a slow list to port as the water rushed in and tilted slightly down by the bow. My damage control party was in the after end of the ship but we were apprehensive and crowded the ladders to get up nearer the upper deck. We had been hit forward of the bridge in the vicinity of ‘B’ turret…the Royal Marines’ turret which had been covered inside with paintings of Walt Disney characters. TRINIDAD was soon on fire from the far side of the bridge to the bow. We went forward towards the sick bay to see what could be done. Hoses were rigged but there was chaos everywhere in the vicinity. The locker flat inside the sick bay was a shambles and forward of that was an inferno. The sick bay had been damaged and the doctors and sick bay staff were shaken and some wounded. There were other wounded men among the wreckage, some of them merchant seamen. I saw one man, supported by his friends, whose lower jaw had been shattered and was virtually non-existent and his feet were hanging limp…a bloody pulp. It was impossible to do anything very positive. I stood transfixed with another rating as we saw a man, not many feet away, screaming his way to death wrapped in the light steel plate of a half bulkhead surrounded by flames. Although we had expected this all day, when it happened the experience was shattering. We did what we could but nothing was very effective. The hoses appeared to be of little use…pressure was low. I imagine the petrol mains which ran from the filling point in the forecastle to the hangar must have contributed to the conflagration. I was told later that the magazine was on fire but I have no way of knowing.

We were attacked again while we were almost dead in the water and one escort of destroyers was circling around trying to drive off the enemy. Destroyers have been called ‘the workhorses of the fleet’. They certainly worked that day. Our guns were still firing and as I made my way aft I saw some sailors sitting on the deck near ‘Y’ turret. They were in a state of shock having been rescued from forward and, in their distress, they hadn’t the will to move anywhere else because where they were sitting they were being rhythmically slapped against the structure by the blast of our own guns which were still firing above their heads. No-one helped or attempted to comfort them…there were more pressing things to do.

I had left my sheepskin coat two decks below near ‘X’ barbette and I went to collect it. I had glanced over the guard rail at the cold forbidding water and had remembered being told once to put on your clothes before you go into the sea. Our station was deserted and in semi darkness it seemed eerie and rather unworldly down there. I saw my friend Blackie Cass curled up in a duffel coat on the deck. I said “What the hell are you doing here?” He replied “I thought I would get some sleep”. I said rather impatiently “Fine time to sleep with the bloody ship sinking!”

TRINIDAD had taken an increased list and we moved along the passageway with difficulty. Several watertight doors were swinging open…bad practice but it was too late to worry about that now. As we were climbing the ladder to the wardroom flat an announcement came over the loudspeaker system “Clear lower decks. Hands prepare to abandon ship”. We were then told to muster on the quarter deck in one section. We passed a glass case in the wardroom flat in which there was a silver bugle presented to the ship on the occasion of her launch. Although, as far as we were concerned, it was the end of the world I repressed the impulse to smash the glass and rescue the bugle. As we reached the open deck we could see the rest of the ship’s company gathering there…some of them carrying treasured possessions. There was a double line of signal flags flying from the port side of the foremast. I idly wondered what they stood for. What dramatic message were we giving to the world?

Passengers and wounded were the first to leave the ship. Everyone was glad that we didn’t after all have to go into the water. The first of our destroyers (FORESIGHT?) manoeuvred alongside in the fairly calm sea and dropped scrambling nets enabling the survivors to jump the gap and clamber aboard. I was in the second batch and got aboard MATCHLESS who immediately wheeled away when she had her share of men. No time was wasted. We were still surrounded by the enemy and it was vital that we kept moving. I heard later that we were attacked by a U-boat at that stage but I was unaware of it at the time or I have forgotten. Finally it was considered that TRINIDAD had been cleared of all who lived. The four destroyers were wheeling in a final circle before heading homeward. I stood with some others near the torpedo tubes on MATCHLESS. She had been ordered to give the coup-de-grace to our stricken ship which was sinking…but too slowly. We couldn’t leave her like that. The torpedo layer trained the tubes to starboard and MATCHLESS increased power and seemed to jump forward like an unleashed greyhound. The order was given and three torpedoes were fired as we raced parallel to the TRINIDAD. After what seemed a long time the first torpedo hit forward followed soon by the second amidships. The ship’s bow plunged forward immediately and the stern rose in the air. As the stern slowly slipped beneath the waves the third torpedo hit and a few seconds later there was nothing left but a swirl of water. Although we were all glad to be alive for another day it was a chilling moment…particularly for me. I had seen her launched and had seen her sink. One of the joiners, Sammy Wills, came along as I was thinking this and asked me if I had seen his friend Les Morris. I said that I had seen him on the upper deck and that he must be aboard one of the other ships. Later I was to discover that Les was in fact among those lost. I do not know to this day whether I had actually seen him or not. It was to become important to Sammy Wills as he questioned me closely in the days that followed. We distributed ourselves around the ship and gradually sorted ourselves out. One of the lascars had a small piece of mat with him and he placed it on the deck pointing to the direction where he imagined Mecca to be.

He got down on hands and knees and gave thanks to his Allah. He did it quite unselfconsciously. It is a pity that it caused some laughter among the British sailors.

The four destroyers sped on their way as quickly as possible. We were to be dive-bombed again before we reached Iceland when we met part of the fleet hurrying north to help TRINIDAD. Regretfully they were a day or so too late but they provided more fire power when we were attacked. Oddly I felt much safer aboard MATCHLESS during the bombing. She moved so fast with so much potential power.

The remainder of the journey was uneventful and we landed at Greenock a few days later. There we learnt the full extent of our losses. I heard that my friend Bill Strong had been killed. He had been in the forward damage centre party. We were housed for a few hours in a large house on the outskirts of the town. I took off my sea boots and stockings for the first time in about a fortnight. My feet were in a terrible state. I threw the boots away and had a bath.

We were given odd items of kit which we required and then embarked on a train for our journey to Plymouth.

END

TRINIDAD sank in the Barents Sea on 15 May 1942

The death toll on TRINIDAD was 1 officer and 62 ratings

Also lost were about 100 passengers…Polish prisoners of war and merchant seamen

There was a large number of seriously wounded

Click to expand photos