Menu

- 10am - 4pm, Mon to Sat

- Adults: £8 Under 18s: £4

- Under 12s/members: FREE

- Pensioners/students £7

- Birchburn, Scotland

- 01445 731137

- JustGiving

Written by Alison Hutchison (daughter)

John Boothroyd

Born 1923 (Yorkshire, UK). Died 2007 (Melbourne, Australia).

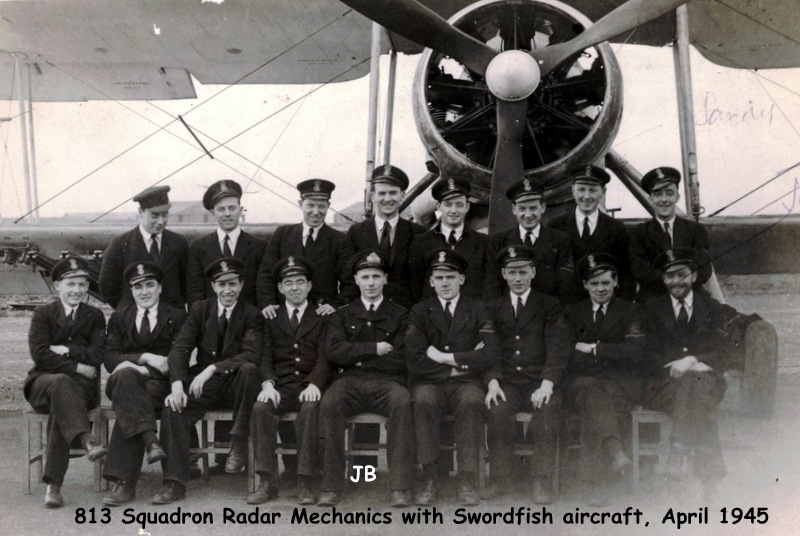

April 1945: Fleet Air Arm 813 Squadron Radar Mechanics on HMS Campania

John Boothoyd is seated in the front row, 5th from left.

Service on Arctic Convoys, 1944-45

Education

Huddersfield College: Higher School Certificate.

St Catharine’s College, Cambridge. MA (Cantab) awarded 1943 (Mathematics and Electrical Engineering).

RNVR Service Record

Appointed 5 July 1943 (aged 20) with the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (there were many RNVR personnel on Arctic Convoys.) Service Record Paper Reference number CW & SRE 901/43. Appointed as an Acting Sub-Lieutenant (presumably in recognition of his University degree, although his education is not mentioned in his RNVR service record.)

Initially appointed to HMS Victory (presumably an on-shore naval training centre), HMS Daedalus, and HMS Ariel, for training courses in 1943/ 44. Qualified as Air Radio Officer and promoted to Sub-Lieutenant on 5 January 1944. HMS Daedalus was a naval air station, also known as RNAS Lee-on-Solent. The base was opened in 1917 and transferred to the RAF in 1918. It was returned to the successor of the Royal Naval Air Service, the Fleet Air Arm in 1939. HMS Ariel was at that time a training establishment established at Warrington in 1942.

Appointed on 15 May 1944 to HMS Campania for Air Radio Office duties with Fleet Air Arm 813 Squadron. Embarkation in Belfast. Service record indicates that he was an Air Radio Officer on HMS Campania and sometimes on HMS Vindex, depending upon where 813 Squadron was required to be deployed.

Promoted to Lieutenant on 5 January 1946. Demobilised on 4 February 1947.

Role and Responsibilities

John described his role with Fleet Air Arm 813 Squadron as being a Radar Mechanic/Swordfish Observer with responsibility for maintaining radar equipment and radio communications for the Swordfish aircraft on aircraft carriers HMS Campania and HMS Vindex.

HMS Campania had over twenty Swordfish aircraft, amongst other aircraft. Swordfish aircraft were torpedo bombers, outdated even in 1939, they were cumbersome, slow biplanes. Nevertheless, they frequently proved effective on bombing raids.

Service on Arctic Convoys

| Outward Convoy | Dates | Return Convoy | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| JW60 | Loch Ewe 15/9/1944; Kola Inlet 25/9/1944; HMS Campania | RA60 | Kola Inlet 27/9/1944; Loch Ewe 5/10/1944; HMS Campania |

| JW62 | Loch Ewe 29/11/1944; Kola inlet 9/12/1944; HMS Campania | RA62 | Kola Inlet 10/12/1944; Loch Ewe ?/12/1944; HMS Campania |

| JW64 | Scapa Flow 5/2/1945; Kola Inlet 14/2/1945; HMS Campania | RA64 | Kola Inlet 15/2/1945; Firth of Clyde 1/3/1945; HMS Campania |

| JW66 | Tail o’ the Bank, Firth of Clyde 16/4/1945; Kola Inlet 28/4/1945; HMS Vindex | RA66 | Kola Inlet 29/4/1945; Tail o’ the Bank, Firth of Clyde 8/5/1945 (VE Day); HMS Vindex |

Recognition of Service

Russia: Russian 40th Anniversary of Victory in the Great Patriotic War Medal. Awarded in 1985 to British veterans of Russian (Arctic) Convoys by the Russian Government. Received by John Boothroyd in 1988. On the reverse side of the medal, in Russian, is written, “War Participant”.

United Kingdom: Arctic Emblem. The first Arctic Emblem was awarded to British veterans on 10 September 2006 by the United Kingdom. Awarded posthumously in 2007 to John Boothroyd, who died on 19/1/2007, following application by his next of kin, Alison Hutchison. The Arctic Emblem was specially commissioned to commemorate the service of Merchant Seamen and members of the Armed Forces in the icy waters of the Arctic Region between 3 September 1939 and 8 May 1945. Those who served in the Arctic regions were often subjected to especially dangerous circumstances including extreme weather conditions and determined resistance from German forces.

United Kingdom: Arctic Star. The Arctic Star was awarded retrospectively with the first medals presented in March 2013. Awarded posthumously in March 2018 to John Boothroyd following application by his daughter, Alison Hutchison. The medal was awarded for any length of operational service north of the Arctic Circle by members of the British Armed Forces and the Merchant Navy. The qualifying area is defined as 66° 32’ North Latitude and the qualifying period recognises the particular severity of the conditions experienced by those who served in the Arctic.

Recollections recorded in 2005/6

A couple of years before his death, John was living in an aged care facility in the northern suburbs of Melbourne, Australia. A member of the nursing staff started a project to use the internet to undertake searches for information of interest to residents particularly about past events in their lives. John’s first request related to Swordfish aircraft and Arctic Convoys. He soon learned that the word “Google” meant “computer search” and began to ask his daughter each week to “Google” certain bits of information relating to his war service. This process led to some of his recollections about the Arctic Convoys being recorded.

John recalled that in the early 1940’s all University graduates were interviewed by the eminent British civil servant Charles Percy Snow to determine how best their skills could be used in the war effort. It was recommended that John should use his skills in the emerging technology of radar. He joined the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve and was assigned to the Fleet Air Arm Squadron 813. He was sent to a “very posh” navy uniform outfitter/ tailor (Gieves and Hawkes) in London to be measured for a uniform.

HMS Campania was an escort carrier built in Belfast. She was launched 17 June 1943 and had been converted from an incomplete hull of a refrigerated cargo ship. She was commissioned 7 March 1944. John was sent to Belfast for embarkation.

In order to get to HMS Campania John had to travel from England to Belfast. He was not allowed to tell anyone where he was deployed, nor for what purpose. He recalled that he had been asked to carry some special pieces of equipment for use in radar. At that time (1944) this equipment, the magnetron, was still a top secret part of British radar operations. John remembers them just being called “…those things made in Birmingham”” but the magnetrons were the main valve for transmitting radar (i.e. powerful microwavegenerators). He remembers that at one point on his trip – which involved changing trains and getting a boat – he nearly forgot the magnetrons, leaving them in a train carriage, but he went back to get them just in time.

John had his 21st birthday in June 1944, a few days after joining HMS Campania and also, a few days after the significant event in WWII of the Normandy D-Day landing. John was responsible for working with pilots to ensure that their aircraft radar was operational prior to take-off. John was deeply affected by the fact that the very first pilot whom he assisted with his radar prior to take-off from HMS Campania (while still docked in Belfast and in good weather) never returned. It was assumed that the pilot, who had been on several Arctic Convoys chose to ditch his aircraft rather than face another Arctic Convoy. This brought home to John the horror of what lay ahead.

When asked about his Arctic Convoy experiences in late 2005 and 2006, John remembered all of the convoy reference numbers (JW60, RA60 etc) immediately and some of the most significant events on each convoy.

He was on four return trip Arctic Convoys from 15 September 1944 to 8 May 1945. His service record indicates that he was an Air Radio Officer on escort carrier HMS Campania and sometimes on escort carrier HMS Vindex, depending upon where 813 Squadron was required to be deployed/ embarked. Convoy JA64/RA 64 was the most dramatic and traumatic. JW66/RA66 was the last wartime Arctic Convoy.

John described his role as being a Swordfish observer – maintaining radar equipment and radio communications for the Fairey Swordfish aircraft on HMS Campania. HMS Campania had over twenty Swordfish aircraft, amongst other aircraft. Swordfish aircraft were torpedo bombers, outdated even in 1939, they were cumbersome, slow bi-planes with the nickname “Stringbags”. Nevertheless, they frequently proved effective on bombing raids.

John’s first Arctic Convoy (JW60) left Loch Ewe in the Northwest Highlands of Scotland on 15 September 1944. The convoy consisted of two dozen Liberty ships (American), several British tankers, a Norwegian tanker, a British freighter and a rescue ship. The naval escort consisted of the escort carrier HMS Campania, anti-aircraft cruiser, about eleven British destroyers, two Canadian destroyers and a battleship6 HMS Rodney. The convoy proceeded north of Bear Island and on to Kola Inlet. He recalled a surface threat from the German battleship Tirpitz which was why the convoy was supported by the battleship HMS Rodney. John recollects that a Swordfish aircraft was lost at sea – it went out and just did not return. There was no loss of merchant ships. On the return trip (RA60), he recalled German submarine U921 sank as a result of actions by HMS Campania. All hands were lost (51 men). Possibly it was sunk by a depth charge or by action from Swordfish aircraft.

On JW62, there was again no loss of merchant ships. But on the return trip (RA62) a U boat (U365) sank the British destroyer HMS Cassandra. Then a Swordfish from HMS Campania bombed and sank the German submarine U365. All hands were lost (50 men). This trip was in mid-December 1944. John vividly recalled that Swordfish planes often missed their return landing in the intense cold and dark. Crew members were frequently lost as planes ditched into sea. Again, no loss of merchant ships on the return voyage.

Opposition to convoy JW64 in February 1945 was fierce. A Wildcat plane from HMS Campania was shot down. There was a strong German attack off Bear Island. Intense snow and poor weather. Then there was a U-boat attack off Kola Inlet. Two British warships were lost and American Liberty ship lost.

The return voyage RA64 was particularly memorable. John was on deck and watched as a corvette, HMS Bluebell, was sunk by a torpedo from U711. The ship sank in 30 seconds with over 80 men lost. There was only one survivor. As John said, to see the ship there one minute and gone the next was an extraordinary experience. The conditions weathered by RA64 were reported to be the worst endured in the entire North Atlantic theatre. The convoy was hit by two hurricanes. HMS Campania rolled 45 degrees each way and equipment and men were flung in all directions. There was concern about leaking fuel from motors and other equipment that had been upended. It was a harrowing experience. John wrote the following about the storm (on the back of a photograph of HMS Campania): “The waves in the worst storm of the war, Feb 45, were twice the height of the flight deck – hence 60 foot high! I decided that when people like the Senior Engineer looked worried, it was time for me to be worried. The 45 degree roll each way was very slow. Crossing the ship below decks one hung on and when level, run like hell and hang on again.” Official records confirmed that escort carrier HMS Campania rolled 45 degrees one way and 45 degrees the other way.

For convoy JW66, 813 Squadron was assigned to escort carrier HMS Vindex. The convoy encountered U-boats around Kildin Island. British and Russians used tethered mine-fields and deep water depth charges to attack U-boats. John said that a new gadget called sonobuoy – a remote transmitting device – was deployed to listen for U-boats. His final voyage was on RA66 which was the last convoy during wartime. Sixty years later, as part of a nursing home assessment, John was asked “Where were you and what were you doing on 8 May 1945, VE Day?” John promptly replied: “Standing on the deck of HMS Vindex as it steamed up the Firth of Clyde at the end of an Arctic Convoy.” The whole crew was standing in formation on the deck of the aircraft carrier as it came into dock at the Tail ‘o the Bank near Glasgow. And there was a huge party that night.

One Google search that John asked for related to Rear Admiral Rhoderick McGrigor who had been in command of the escort vessels from HMS Campania. John expressed enormous admiration for McGrigor’s personality and leadership under terrible conditions. Here is a link to a photograph of Rear Admiral McGrigor on HMS Campania.

Subsequent Career

Following experience with radar during World War II, John went on to work (in London) for A.C. Cossor a British electronics company, and then he went to English Electric (in Kidsgrove, Staffordshire) where he contributed to the research and development of the DEUCE Computer. DEUCE (Digital Electronic Universal Computing Engine) was one of the earliest commercially available British computers, built by English Electric from 1955. John would be called out to fix a computer in some distant part of the country when the multiplication/division component malfunctioned.

John emigrated to Hobart, Tasmania, Australia in 1964 and took up the position of Officer-In-Charge of the Computer Centre at the University of Tasmania/ Hydro Electric Commission.This was the first public sector computer in Tasmania. In 1975 John retired on the grounds of ill health, not unrelated to his wartime service, age 52 years.

Photographs

1944: Fleet Air Arm 813 Squadron on HMS Campania.

John Boothoyd is seated cross-legged on the ground in the front row, 4th from left.

Extract of John’s RNVR Service Record Front Page.

Click to expand photos