Menu

- 10am - 4pm, Mon to Sat

- Adults: £8 Under 18s: £4

- Under 12s/members: FREE

- Pensioners/students £7

- Birchburn, Scotland

- 01445 731137

- JustGiving

Written by Patrick Shirley (son)

Two World’s Collide – Patrick Shirley

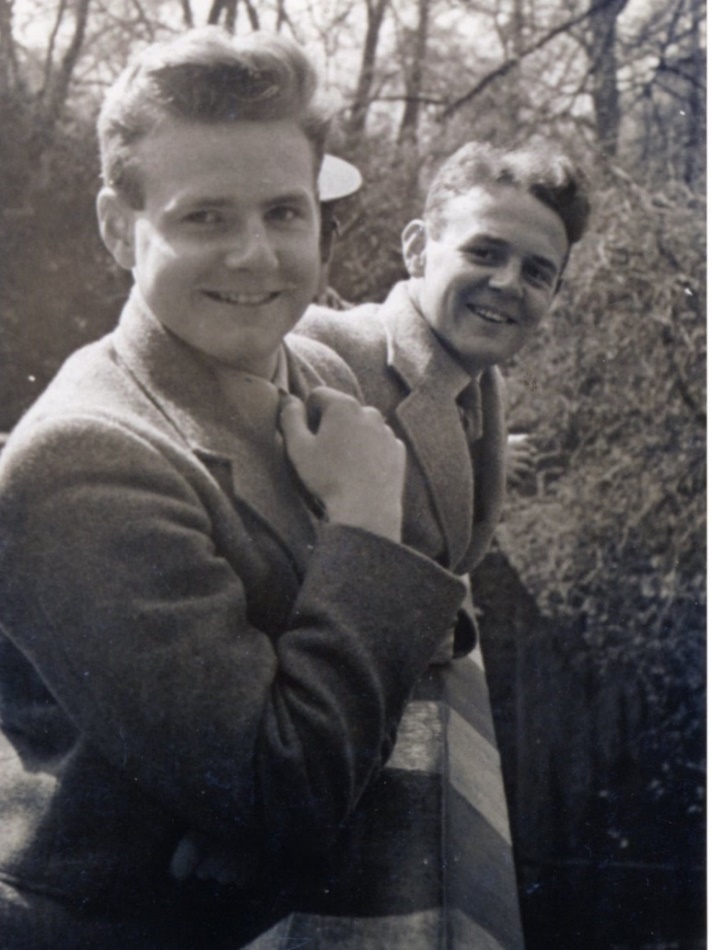

The opportunity to finally compose this true story came during the Coronavirus pandemic and the 75th anniversary of VE Day. It seemed an appropriate time to compile in parallel two accounts of the WW2 Arctic maritime conflict. This was a war that any participant was very fortunate to survive; battling the enemy and also the sea and elements. The two narrators are my father, John or “Jack” Shirley, a second lieutenant in the Royal Navy serving on the corvette K-405 Alnwick Castle and the Mechanical Engineer, Herbert Lochner, serving on the U-boat U-425. This is a story of their relative experiences of war from a very young age; both were close to their 18th birthdays in 1940, through to their relative survival of the war, with a common conclusion, that they were the “lucky” ones.

It seemed to make sense to start with my father’s account up to the sinking of U-425. I have then introduced Herbert Lochner’s account prior to the sinking. The two accounts of the sinking are then presented in parallel when both their worlds ‘collided’. Finally, their separate accounts following this event that brought them together and their separate histories to the end of the European conflict are included.

It remains to sincerely remember those on both sides that died in this conflict and pray that there is no repeat in any of our future generation’s lifetimes.

Patrick Shirley’s book, Two Worlds Collide: A Richly Illustrated True Story of the Arctic Convoys and the German Submariners in WW2 was published in 2022 and is available on Amazon.

The convoy emerged from the Kola Inlet in the early morning, having received early reports of U-boat activity outside. The late night was black, and a slight sea was running.

We were in company with HMS Lark. An asdic contact was made by Lark. It was passed on to Alnwick Castle. We mounted a ‘squid’ attack. After a short interval, the U-boat began to surface, conning tower first, visible in our searchlight. Men were emerging, some diving into the water, others seemed to be trying to man the gun. Tracer was fired at the conning tower – it was stopped when the activity stopped. Men in the water were calling out. Some had yellow clothes, some blond hair.

We launched our ship’s boat, first lieutenant in charge. The wooden snow cover had to be removed first. The sinking U-boat was perhaps two cables away (400 yards). The men in the water were disappearing fast. When the boat returned, one survivor had been picked up alive.

The survivor was taken, unconscious, to the sick bay. His clothes were cut off (several layers). He disclosed his U-boat’s number (U-425), that is all.

He was called Herbert Lochner. The SBA was able to resuscitate him by massage. The sole survivor of U-425 was Herbert Lochner. He was a technician petty officer whose hometown was Danzig. He was a prisoner of war until May 1948. Many years later, he wrote an account of his experiences and I was shown a copy by a naval officer who was researching these wartime events. On the whole, the account is objective, but I felt it obliged me to write the account of the action as I observed it. Herbert Lochner did appear to believe that the British could have done more to save his comrades, even though he seemed to be fully aware of the extreme Arctic conditions on the night in question. Herr Lochner wrote an article for a German magazine in 1993, not long before his death. We were privileged to meet his widow Frau Lochner in 1996.

The following is a precis made from Herbert Lochner’s account:

“At 10 pm we were lying on the surface. On receiving a radio message, we dived to 40 m. It seemed the Red Army were approaching Danzig, my hometown. Lying on my bunk. Oxygen problem in the U-boat. Under silent regime. Dozing. Soon after midnight, propeller noise heard above. Also enemy asdic transmissions for some time. Suddenly, depth charge explosions – the lights went out. Tilted 40–50° towards the stem. I went forward to torpedo compartment to repair a leak. Emergency lights came on. Faces of my comrades showed pale in the light. Depth meter showed we were lying below 200 m (I went paler!). My young apprentice sat between the tubes, looking frightened, with wide eyes, rosary in his hands. Silence, straining to hear from control centre.

“Then, order came ‘All hands to forward end’, water had flooded main engine and electrical compartments in stem of sub. Trim was not greatly improved by crew moving forward. Then, more depth charges – sinking confirmed. Waiting helplessly. No panic. Sound of creaking in hull, due to water pressure at depth. Smell of gases from damaged batteries. I sat on my bunk, took out my diving rescue kit from its bag, remembering training at Pilau Sub. School (in favourable water conditions, and only 40 m depth!) – ‘Come up, slowly.’ But U-boats normally operate below 100 m. Thinking and hoping! It is possible to use compressed air to bring the boat to the surface, before sinking has happened, in fact. The commander knew this was the only hope of rescue. Crew collected in HQ area below conning tower. Compressed air brought boat to surface, slowly, very slowly. Relief showed on the men’s faces, as ascent showed on gauge. 18- to 19-year-olds looked old and haggard. Commander: ‘We’re coming up… get out as quickly as possible… don’t forget your rescue kit.’

“A few minutes to surface – hatch opened – fresh air entered noisily. All realise, little time left for survival. We put on lifebelts, ran to hatch – no panic I was about 35th out. Sub lay stricken stem down. Commander stood by binocular stand, flung distress flares into water. Men standing on conning tower and storm deck. Oerlikon tracer fire still from British. Firing ceased after flare hit water. Many men in water. Next me, a security officer did not know how to use his lifebelt. I helped him, but his compressed air cylinders were empty. Some tried to launch rubber dinghy. Water already reached guns. I climbed to the bridge, with two others. We were the only ones left. I remember the advice when I served in a destroyer, ‘Stay on board as long as possible.’ When the bridge submerged, we swam for our lives. The sub sank, bow in the air. Obersteuerman, who had been witness at my wedding, was without lifebelt; he held on to my shoulders for some time, then I realised he was no longer there. A few men were still swimming, shouting ‘Help’. Some tracer shots were still fired, but why? The water was very cold; my legs became stiff. I took photos from my pocket and threw them away, to prevent them falling into enemy hands. I had a few words with my friend, Mayazusieke, ‘Maybe will make it?’ Then calmness, in the foamy water, for how long?

“I opened my eyes. I was lying in the bottom bunk of the sick bay of the corvette (Alnwick Castle). Quickly conscious. White sheets. Several seamen in waterproofs were in the room, looking curious. I was well cared for.”

Click to expand photos