Menu

- 10am - 4pm, Mon to Sat

- Adults: £8 Under 18s: £4

- Under 12s/members: FREE

- Pensioners/students £7

- Birchburn, Scotland

- 01445 731137

- JustGiving

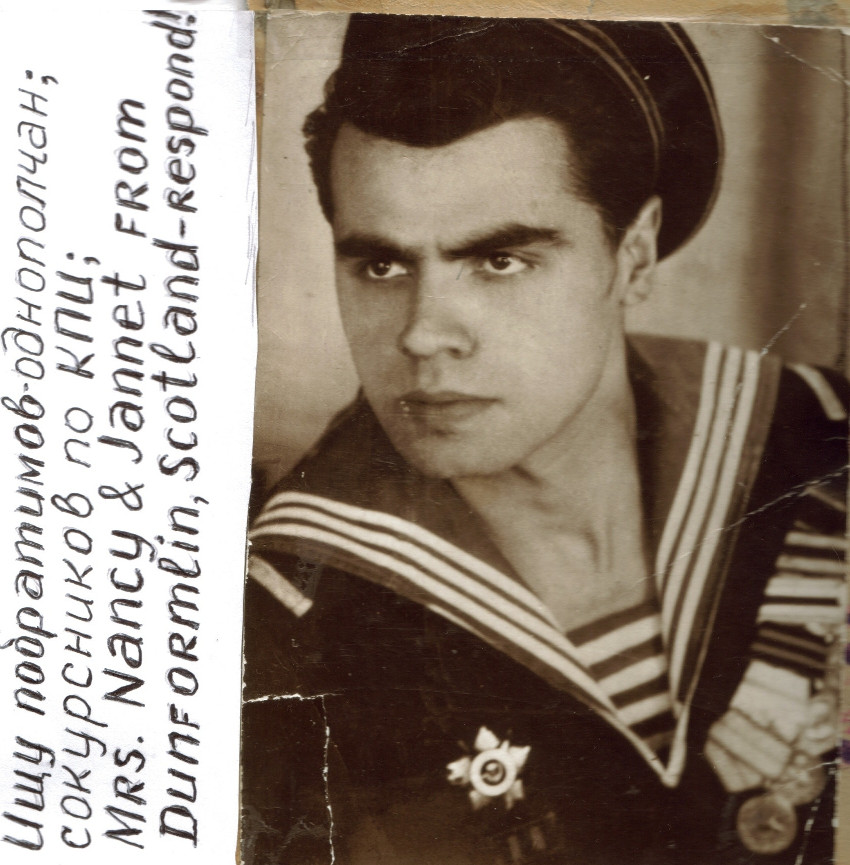

Extracts from Konstantin Dzhagaryants’s memoirs, under the title “Odyssey of a Soviet Navy Seaman. Part 1: aboard HMS Royal Sovereign (Arkhangelsk), 1944”. He travelled on RA-59 to Scotland to board HMS Royal Sovereign, being temporarily transferred to the Soviet Navy, and return to North Russia. These selected chapters deal with some of his impressions of Scotland and Royal Navy men. 19. The entire crew has arrived. Another day passed. From the “Empress of Russia”, our crew continues to arrive in separate groups. Soviet cooks appeared in the galley and began to work together with British ones. Our stewards were allocated separate dispensing windows in the galley for receiving ready-made food. There were two separate queues at the dispensing windows - ours and the British one. At lunchtime, immediately after the meal, there are two lines again! This time, for the top-up: ours - for the first or the second course, the British one - for the additional ration of rum. After an hour and a half or two, you could drink coffee or tea in thick white porcelain mugs. Drinking from them was a pleasure: it was feeling like home. Especially after our navy and army issue mouth-burning aluminium mugs. But finally, the whole crew arrived from the “Empress of Russia”- 1600 people. We learned about this from an unusual situation in the galley. At lunchtime, a noisy line of Englishmen formed at their dispensing windows, where it was always quiet and calm. This had never happened before! We watched the busy place with amazement. An officer explained that the whole crew had already arrived, and our cooks took over the watch in the galley. The Brits loved the food they cooked. And so, they came together for lunch from all over the ship. My friend Williams approaches me: “Kostia! Oh! Russian borsht! Very well! Exotic!” It turned out that instead of sweetish bean soups and other flavourless food, our cooks made navy style borscht! The British were delighted! I can say they went crazy about it! They were jostling, joking, shouting: “O-oh! Russian borsht”! The closer we got to know the signalman Willy, the more respect we felt for him. A serious, intelligent-looking older guy, he once undertook to educate us. Seeing a Hall anchor tattooed below the elbow on the back of my arm, he said that he did not approve of tattoos on human bodies. From his words we could understand something unflattering for us. Like, this is barbarism, savagery, typical of uncultivated people, teddy-boys and ... criminals. It turned out that their crooks and bandits, like ours, have a specific tattoo (at least they did back then). However, right nearby his own compatriots sported tattoos even of a pale red colour – which we, and even more so, our dandies strongly envied. We also had a friend from the boatswain's team. The Brits affectionately nicknamed him "Little baby" or "Little boy". We called him in Russian "Baby Kroshka", or simply "Kroshka" (which means baby). More than anybody else, he became friends with Ivan Grozenko. "Baby" was about 2 metres tall, he weighed up to 100kg or even more. He was a strong and sturdy good-natured guy, a little plump, always kind and ready to help if necessary. When we were assigned to the galley to peel potatoes clean after the peeling machine, he used to sit down next to us and help. While doing this, they recalled Stalingrad, Kursk, the battles in the Mediterranean, the Atlantic, in the Indian Ocean. By the way, it was the first time we saw a food processor. At “Parizhanka” (Paris Girl - nickname of the Soviet Navy ship Paris Commune), this work was performed by a duty squad of about twelve people. "Baby Kroshka" was obviously a friend of the Soviet people and their country. 25. Historical farewell. “Captain”. The command sounded over the broadcast: Royal Navy ranks to leave the ship! By that time, the distinguished guests had already left on an admiralty boat to the tunes of Soviet and British marches. The Brits left their tables and went downstairs to get their things. They returned with canvas sacks – long and square in cross-section. Some, having said goodbye, proceeded to the tugboat. However, many of them, leaving their bags there, returned to their tables. They said goodbye again, hugged us, shook our hands. So we led our friends to the gangway - Willy, Bob, Baby Kroshka, and others. We embraced warmly, realizing that we would not see each other again. And on the broadcast again and again the command sounds to the English sailors to leave the ship. But the British sailors are in no hurry. They come back – to hug one last time, to pat on the shoulder, shake hands. The orchestra thunders - at times, even with some sort of a sad note. Then "Katyusha" sounded in English and Russian - amicably, with inspiration, with a full breast. And then from the depths of the wardroom suddenly appeared right in front of us the Englishman whom we knew as "Captain", our teacher and mentor! A warm, friendly farewell followed. Fatherly hugs, pats on the shoulders, handshakes. He says something in English, heartfelt, soulful - he was clearly emotional and probably drunk. Now he is approaching the ladder. He grabs the handrails. Suddenly he turns around and waves to us. And unexpectedly - what is this!? ... We froze ... In pure Russian (!) he exclaimed: “Goodbye, guys! Say hello to the Motherland from a lost Russian soul!” ... Already, almost everyone, including “our” British officers, went to the tug. They are standing at the bulwark, shouting something, waving their hands. Only a few restless desperate sailors, warmed up with rum, obstinately, earnestly did not want to part with the ship and with us. From the middle of the gangway, they return again and again for the last hug with their friends. But no one rushes them ... None of their officers raises his voice. Everyone is waiting patiently... Some have eyes glistening with tears. The sadness of the “Farewell of Slavianka” march excites our hearts. Finally, as the last British sailor left, the jettisoned gangplank thundered across the deck of the tug. A sharp sound, like the clatter and rattle of a coffin lid, divided our friendly worlds for good... The explosive chords of "Slavyanka" sounded with renewed vigour over the waters of the bay. The tug slowly began to sail off. The gap of water grows, reaching several meters. And suddenly from the side of the tug, from all its board, serpentine streamer ribbons flew towards us. Its multi-coloured threads, like a spider web, stretched from side to side, from hand to hand - as if symbolizing the fragile connection of our hearts. The tug quietly and slowly continues to sail away, and the ribbons began to break. New coils of serpentine were already falling into the water. But this had not yet broken the symbolic link: sailor caps flew from the side of the tug. Spinning like a boomerang, they flew towards us, picked up and left as a keepsake. We could not respond in the same way: our caps were state property! I also got an English visorless sailor cap. It was kept in my family for a long time until it got lost in the hustle and bustle of everyday life. But now the tug got so far that a couple of sailor caps did not reach us and floated alone on the water surface. With the long parting whistles, the tug increased its speed and departed, leaving some kind of emptiness in our souls.

Click to expand photos