Menu

- 10am - 4pm, Mon to Sat

- Adults: £8 Under 18s: £4

- Under 12s/members: FREE

- Pensioners/students £7

- Birchburn, Scotland

- 01445 731137

- JustGiving

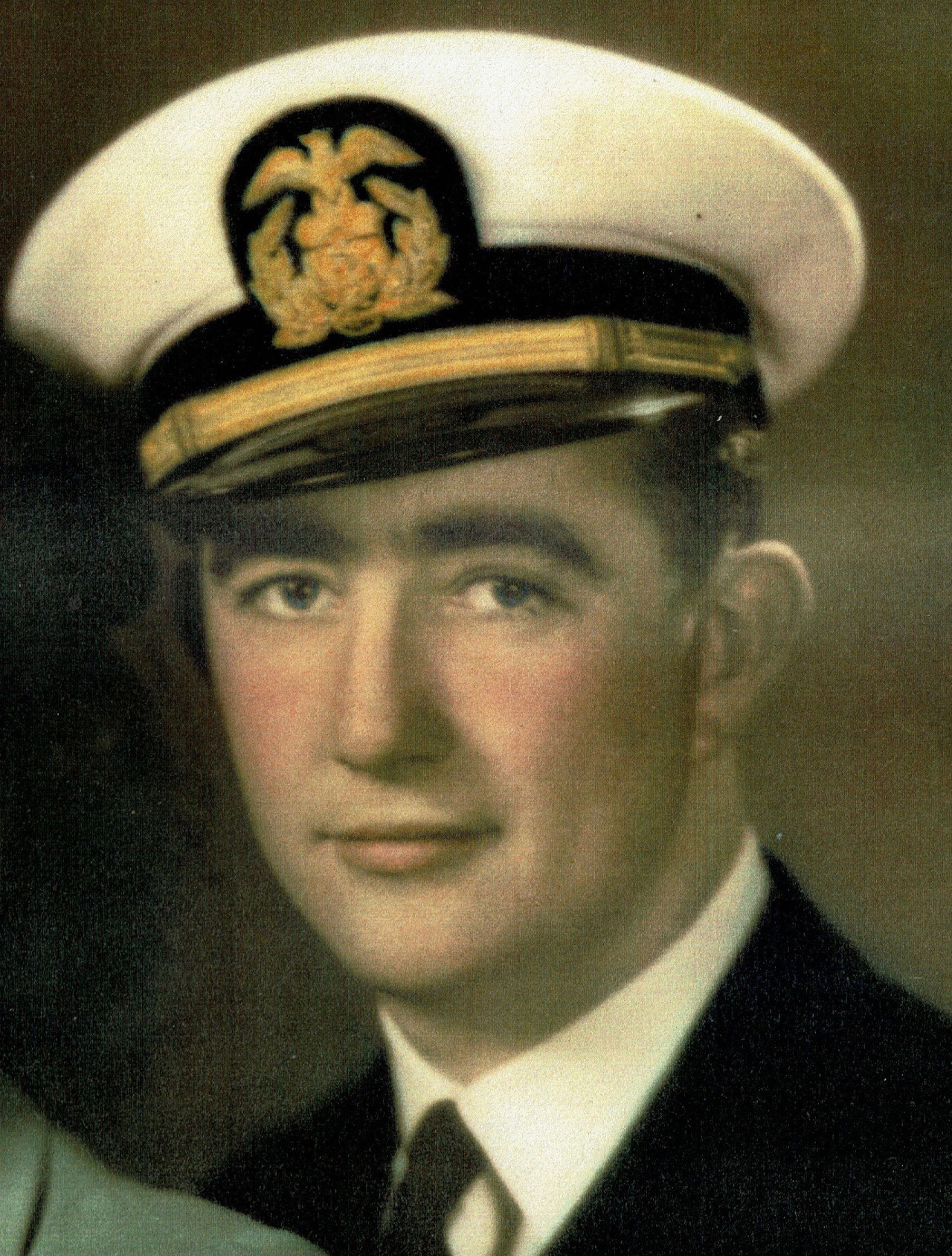

Written by Paul G. Gill Jr. (son)

My father, Paul G. Gill, Sr., was born on July 3, 1920, and died on February 23, 2000. He served as Third Mate on the Liberty Ship SS Nathanael Greene from April 1, 1942 until the ship was destroyed by U-565 off the North African coast on February 24, 1943. The Greene sailed to Archangel in Convoy PQ18, in September, 1942. During that voyage, she was credited with destroying 8 enemy aircraft. After the war, the Nathanael Greene was designated a Gallant Ship of World War II, one of only 9 merchant ships to be honored, out of the more than 4,200 that served during the war.

Here is an anecdote from my father’s book, Armageddon in the Arctic Ocean. My eyes well up with tears no matter how many times I read this story:

“The force of the Mary Luckenbach explosion was terrifying. Our vessel was lifted from the sea and shook violently as the obliterated ammunition ship rained down on us in the form of shrapnel. We were enshrouded in a dense cloud of black smoke. The air was saturated with dust and fouled by the acrid smell of gunpowder. We didn’t know whether the Nathanael Greene was going to remain afloat or plunge to the bottom of the Barents Sea.

“We climbed over the gun nest wall onto the poop deck, and then dove over the rail to the main deck below and crawled under cover. Ten thousand tons of ship and cargo had been pulverized and blown sky high in an instant and were now falling from the heavens, covering our ship and the sea around it with what had once been the S.S. Mary Luckenbach. Tons and tons of shrapnel continued to fall about us in every size and in cruel and grotesque shapes and patterns.

“The smoke around our gun nest gradually cleared, but the bridge and midship housing were still invisible. The afterdeck rigging was in ribbons. The crates encasing the fighter planes, which had been chained to the cargo hatches, had disintegrated, and the tanks destined for Stalingrad were adrift of their anchor chains. Everything within sight was battered by the concussion and vacuum created by the explosion. Our clothing was ripped and torn by the blast, and saturated with shrapnel. The forward part of the ship must have been blown to bits.

“I looked over the ship’s side and saw the propeller slowly turning. Not knowing whether we were going to sink or remain afloat, I didn’t know what we should do: dive overboard and swim clear of the sinking ship’s suction, or hang on and wait for rescue by a destroyer. The latter seemed unlikely, considering how quickly the enemy pounced on and destroyed crippled merchant ships during yesterday’s combat action.

“As I pondered our fate, the dense black smoke started to dissipate and the rain of shrapnel subsided. Looking forward, I could make out the outline of the bridge. I was surprised that it was still there. Then, I heard the ship’s whistle signaling us to report to boat stations. I made sure that all the men in the after gun stations were accounted for and on their way to the lifeboats.

“Thinking the Greene herself had been torpedoed, the captain ordered ABANDON SHIP, and the crew manned the lifeboats. Before leaving the gun station for the lifeboats, I remembered one last thing I had to do. When I was on watch the night before, Captain Vickers said to me, ‘Mr. Gill, during today’s battles I noticed that none of our American ships, or those of our allies, flew their ensign. Now, if we had our Stars and Stripes flying from the gaff…’‘

“I replied ‘Aye, aye, Sir!’ and promised that when we went into battle again I would make sure the Stars and Stripes were flying. In the chaos of today’s combat, I completely overlooked my commitment to the captain. Now that the ABANDON SHIP alarm had been sounded, and the crew was manning the lifeboats, I remembered my orders and made my way to the mainmast. I removed the ensign from its locker, bent it on its halyard, and aloft she went! When the men saw the Stars and Stripes flying from the gaff of the mainmast they broke out in cheers. I felt a lump in my throat and was overwhelmed with emotion. I thought, “What heroes! We have so much to fight for!”

“Captain Vickers gave orders to the chief engineer to stop the ship’s engines and make a quick survey of the mechanical equipment and the integrity of the watertight compartments. I mustered the men assigned to my lifeboat, made sure they were all there, and awaited further orders from the captain, who I could see on the wing of the bridge.

“Some of the men were seriously injured. One member of my aft gun station had a huge piece of shrapnel embedded in his back and another had an arm that had been shredded by enemy machine-gun bullets. But there was no time to fully survey and document all of the crew’s injuries.

“Several of the injured men had made it to their lifeboats and collapsed to the deck. The two ship’s cooks suffered severe head injuries, and two of the naval armed guard sailors were all shot up by enemy machine gun fire. When I looked around, I could see even more casualties. Someone reported seeing Willy, one of our messmen, being blown off the foredeck into the sea by the explosion. Many men had had their helmets torn from their heads by the violent concussion, and all that remained was the chin straps and cotton padding. Helmets worn by crewmen in the interior of the vessel were rippled like washboards, stark evidence of the violence with which the explosion had tossed these men around inside the steel confines of the ship.

“We did our best to control bleeding from the most grievous wounds and to splint fractured limbs. We gave morphine to the most seriously wounded men, and were amazed to see that many men with serious injuries had no idea they were injured. Meanwhile, we still didn’t know whether or not we had been torpedoed. The ship’s engines were still working, the propeller was turning, and the steering gear was working. Maybe there was hope for the Nathanael Greene!

“Captain Vickers sounded the ship’s whistle for dismissal from boat stations, and then he rang up FULL SPEED AHEAD on the engine room telegraph. We were going to attempt to catch up to the convoy. Those who were capable of standing watch were ordered back to their gun stations. The air was heavy with suspense. Would the Greene make it back to her position in the convoy, or would enemy aircraft circle back to administer the coup de grace, as we had seen them do repeatedly in yesterday’s fighting?

“The men on the other ships in the convoy cheered and cheered as we caught up with them! The Stars and Stripes were still flying over this Yankee, so horribly scarred from battle with the enemy, with rigging hanging from the masts in threads, portholes blown in, heavy exterior oak doors blown off, liferafts blown away, and its decks strewn with debris from its shattered deck cargo and the shattered remains of the Mary Luckenbach. All that mattered to us now was that we were still alive and afloat, and that we were going to make it!”

After returning to the United Kingdom in November, 1942, the SS Nathanael Greene sailed in convoy to the Mediterranean to deliver munitions to Mostaganem, Algeria, in support of Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa. She was torpedoed by U-565 on February 24, 1943, and towed to the beach near Oran in sinking condition by HMS Brixham, and was declared a total loss the next day. After the war, the SS Nathanael Greene was designated a Gallant Ship of World War II, one of only 9 merchant vessels to be so honored. A plaque honoring these vessels and their crews was installed in the Gallant Ship Room at the American Merchant Marine Museum at Kings Point, New York.

The painting was the work of the American marine artist, Herb Hewitt. I commissioned it in 1992 and presented it to Dad at Christmas. He was deeply touched.

Click to expand photos